Aristotle says that art is the “imitation” and “perfection” of nature which has always struck me as a highly evocative and mysterious way to put it.1 Of course, the word “art” (techne), in this case, means more than what we understand in English as “fine art”, or “the arts”, including “craft”, and as the Greek might suggest, “technique”. It is also the root of the English word, “technology”.

That art imitate or perfect nature is, perhaps, easiest to see in crafts and techniques. Consider, for example, the art of horticulture, which imitates the natural process by which plants reproduce and are nourished, but also intensifies, strengthens them through irrigation, fertilizers, or even something as simple as pulling weeds. In these art-ificial processes, nature is “perfected” and a plant is drawn into a state of flourishing far beyond (sometimes absurdly so) what is possible according to nature’s processes on its own.

But what about the fine arts—music, painting, poetry, and film? In what sense are these imitations and perfections of nature. It is somewhat commonplace in art history to talk about the ways that the “realism” (or, better, mimesis) of Aristotle’s art-as-imitation has been supplanted in more recent eras by the newer understanding of the artist as one who illuminates, and expresses (expressing especially the self). What I find unsatisfying in these over-simple accounts of art history is the ways that they pass over the second part of Aristotle’s definition—art as nature’s perfection. Art, for Aristotle, it would seem, involves far more than “a realistic style”.

In Aristotle’s Poetics, he explores the purpose, structure, and effects of tragic drama, which produces in its audience a suffering that leads to the experience of catharsis, or cleansing. That is, through the imitation of suffering on stage, the passions of suffering which cleanse the soul—a fear transformed into pity—are perfected and brought to completion.

Now, this kind of catharsis belongs, for Aristotle, to the highly specific and ritual context of Athenian tragic drama offered as a form of worship to the god, Dionysus. Even so, if we remember that “to suffer” is merely “to pass through something”, I think that Aristotle is still very close to us when we try to create in the modes of illumination and self-expression. What is it that we are trying to express in a song or a poem? Nothing, I would think, but the motions of the soul as it experiences or suffers the world. The work of art captures and makes perfect this encounter so that the souls of others who experience it may be drawn into and pass through the same motions, and in the best cases, like Aristotle says, be cleansed by them.

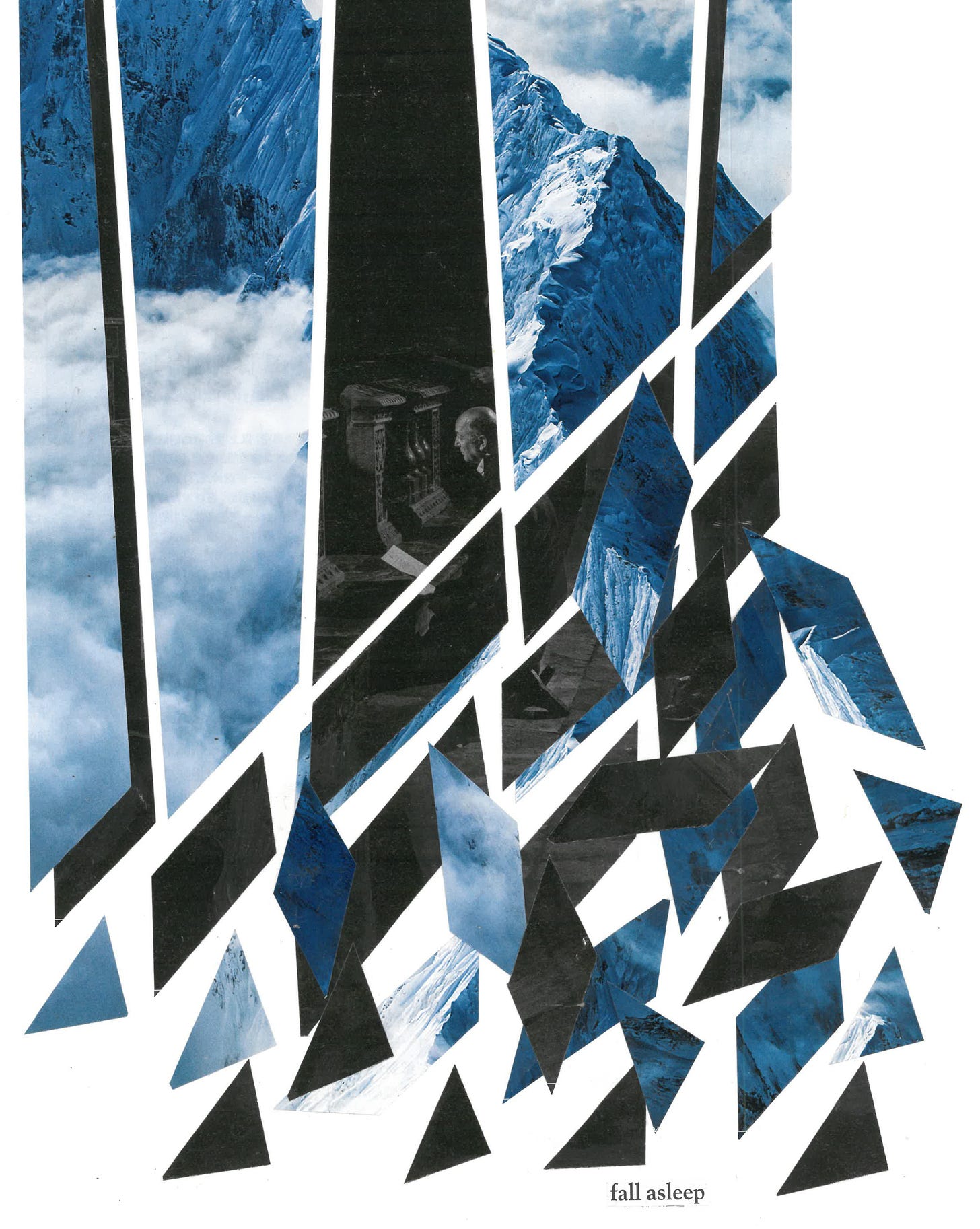

An encounter with a work of art has the power to rinse off the stupor of ordinary life, the dullness that habit and familiarity bring (which, of course, is no fault of the world, but arises from our own mistaken assumption that we already know “what is”). Through the world of the work of art, which is only ever an imitation of the world as it is undergone by some soul, our own encounter with the world is made perfect or real once again.

“The Grey Line” in its first week on earth

My new song, “The Grey Line”, a country-folk eulogy to the long-lost Canadian Greyhound bus lines, came into the world one week ago. Thank you all for listening to, sharing, and (as the Lord wills) enjoying this song, the first of its kind to appear from myself since entering exile over ten years ago as a Grad student.

Some of my favorite feedback so far:

“Canadiana! The world needs more of this.”

“Very Stan Rogers and Gordon Lightfoot.”

“I more than like it. I am slain.”

It is still very early days, both for this song and for this whole experiment of “re-emerging” to share music on the internet again. Anything you do to share and interact with “The Grey Line” is a huge encouragement to me and the project.

I’m also very proud to share that the song has been featured in the latest film by Levi Allen (my brother!), who over the weekend released his long-awaited adventure-documentary epic about being dropped alone into the Spatsizi Wilderness of Northern British Columbia with nothing but a fly rod, a dinghy, and some film equipment (no food!) .

A few of my songs appear in this movie, but “The Grey Line” appears at a very exciting moment about thirteen minutes in. I highly recommend popping some popcorn and settling in for this wild and wonderful ride.

See, for example, Physics II.8, 199a:

“Thus if a house, for example, had been a thing made by nature, it would have been made in the same way as it is now by art; and if things made by nature were made not only by nature but also by art, they would come to be in the same way as by nature. The one, then, is for the sake of the other; and generally art in some cases perfects what nature cannot bring to a finish, and in others imitates nature. If, therefore, artificial products are for the sake of an end, so clearly also are natural products.”